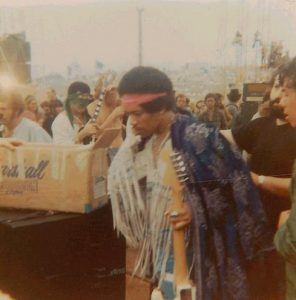

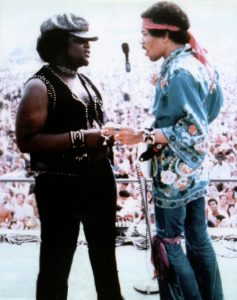

As the sun rose over “Woodstock Nation” at Max Yasgur’s farm on the morning of August 18, 1969, Jimi Hendrix took the stage.

He was supposed to close the momentous three-day festival the previous night, but the concert ran so far behind schedule that he ended up saluting the dawn instead. With the crowd having thinned to about 30 000 from its estimated peak of a “half million strong “Hendrix looked out on field in which it was difficult to distinguish between people and debris. Those who had stuck around to catch his set saw a different Jimi Hendrix from the one who burst on the scene at the Monterey Pop Festival a mere two years earlier.

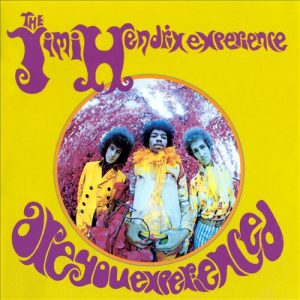

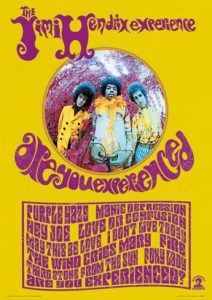

For starters, his band, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, was no more. They had performed their final show in June, and Hendrix had been holed up during the summer jamming with new musicians and pondering his future direction.

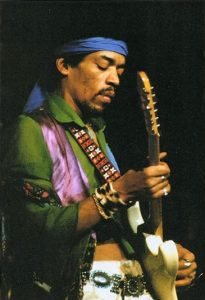

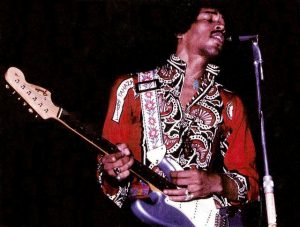

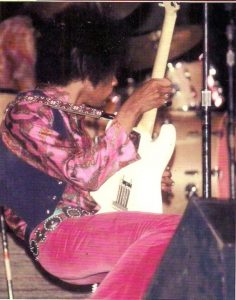

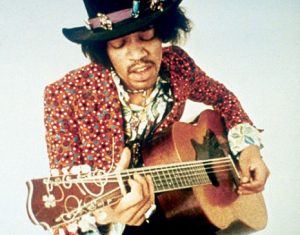

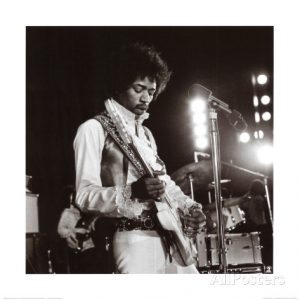

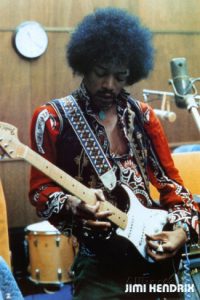

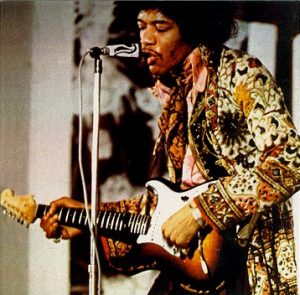

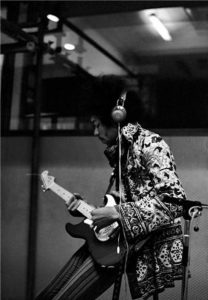

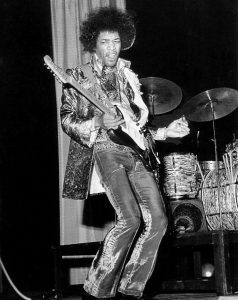

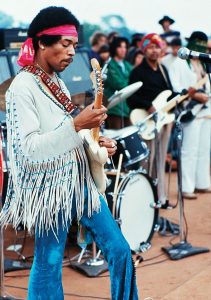

He came to Woodstock with a five piece band that he introduced as the “Gypsy Sun and Rainbows”. It included bassist Billy Cox and guitarist Larry Lee, whom Hendrix had played with during his army days in Tennessee, and drummer Mitch Mitchell from the Experience. Two additional percussionists, Juma Sultan and Jerry Valez, had been enlisted by Hendrix to expend his power trio sound. Although Hendrix flicked his tongue at his guitar now and then, he was physically subdued on stage. This performance showcased Hendrix the guitar virtuoso. The set mixed hits (Fire), blues (Here My Train A-Comin) and new songs (Message to Love) with some extended improvisations (Jam Back at the House).

Hendrix’s appearance was most memorable, however, for his astonishing interpretation of “The Star-Spangled Banner” which was used to close the 1970 film Woodstock. By default it was also to be fitting close for a tumultuous decade.

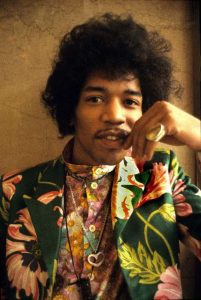

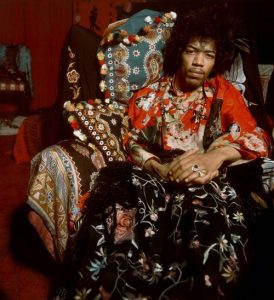

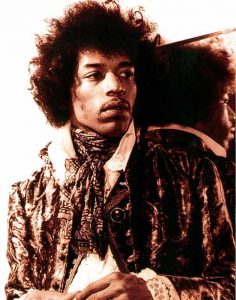

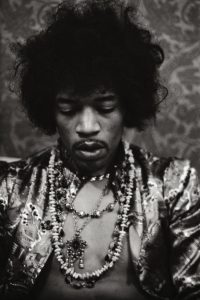

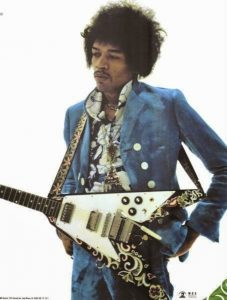

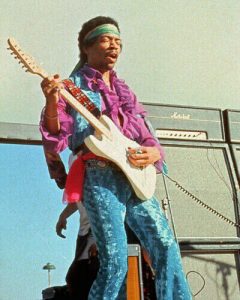

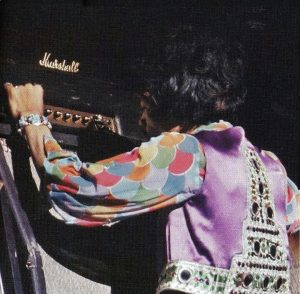

The image of Hendrix playing national anthem has become symbolic of the counterculture. He looked as funkily elegant as always, sporting an Afro banded by a red silken scarf, an Indian-fringed suede jacket, blue velvet bellbottom pants, beads, and silver earrings in both ears.

- JIMI HENDRIX, 1973.

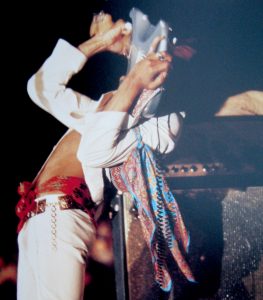

Hendrix began his instrumental version of the song by flashing a peace sign to the audience. Then accompanied only by Mitch Mitchell, psychedelic jazz drumming, he played the first few verses of the song, adhering closely to its familiar form. When he got to the line “and the rockets red glare” Hendrix let loose with a carefully orchestrated sonic assault on the audience in which his shrieking, howling guitar riffs, modulated and distorted with feverish feedback, attained the aural equivalent of Armagedon. The bombs bursting in air and ear transformed Yasgur’s placid cow pasture into the napalmed and shrapnel-battered jungles of Vietnam. As the song drew to a close, Hendrix solemnly intoned a few notes of “Taps” memorializing not just the slain but perhaps his own former pro-war stance that dated back a few years to his hitch in the army.

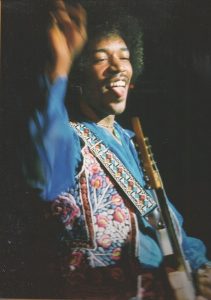

The crowd was stuck dumb by this bravura deconstruction of our national hymn, which managed to simultaneously evoke chauvinistic pride for and unbridled rage against the American way of life. These seemingly incompatible feelings found a tenuous resolution in the early morning air of the day in late summer during the Nixonian denouement.

When asked a few weeks later why he played the song at, of all places, the Woodstock Festival, billed as “3 Days of Peace and Music” Hendrix responded “Because we are all Americans …”

When it was written it was very nice and beautifully inspiring. Your heart throbs and you say “Great that I’m American ‘.

BY LAUREN ONKEY