‘Apocryphal Declaration’ rocks America

By Anna Key in Washington

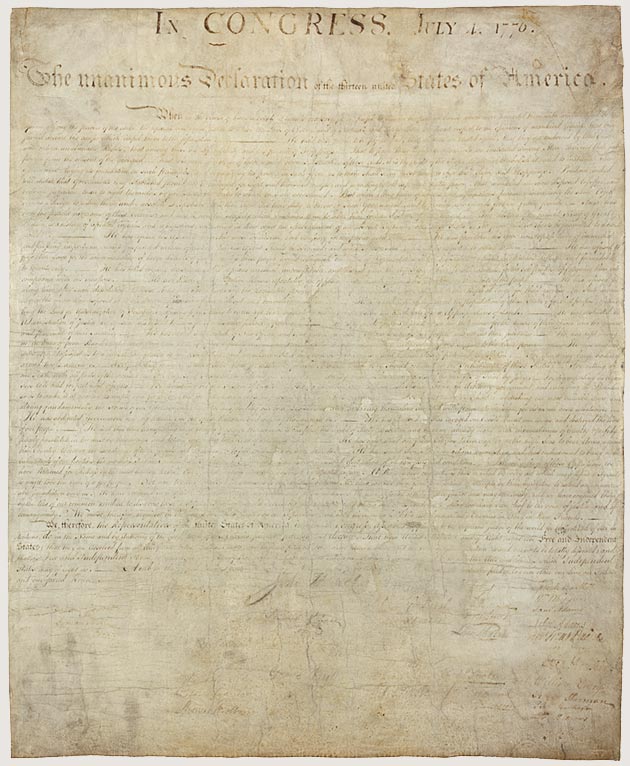

Liberty is ‘ours to secure’, papers say

Citizens of the remaining States of the Union of Gettysburg may have “unalienable rights” to life and happiness, according to controversial declassified documents.

The papers, discovered by a chimneysweep at the Cheney Library of Constitutional Studies, suggest that the Union’s founders were at odds with the ruling Latter Day Church of Obamination.

“All men are created equal,” says the collection’s principal manuscript, a draft entitled “Declaration of Independence.”

Although it resembles an artifact already cited by historians, one significant difference has touched off a debate more polarised than any since the Republic’s last president came out as an atheist Bible-basher.

The text refers to a “necessity” for Post-Americans to “alter their former Systems of Government” because of “a long train of abuses and usurpations.”

Scholars say this message contradicts the Church’s Obama Doctrine of pre-emptive pacification. Instead of preaching faith in His power to lead the world to Freedom, it asserts that all citizens are “endowed by their Creator” with a right to “the pursuit of liberty.”

This line in particular has sparked fierce debate among delegates to the Post-National American Congress (PNAC).

Some want the principle to be canonised, alongside other founding values like enslavement. Others dispute its heritage, citing the elder Reverend Clinton’s view that the papers are “apocryphal and borderline Satanic.”

A person familiar with the Cheney Library’s thinking dismissed the draft Declaration as “quaint”, and said it had been written “on hemp”.

—————————————————————————-

You’ve been framed…

How news works: The manipulation of media by propagandists is an old story, but it’s getting more professional as commerce bankrupts journalism, robbing it of democratic value, writes Raoul Djukanovic

‘Newspapers generally lie because people lie to them’

‘You can report anything that a source says, regardless of its veracity, provided that you report accurately what the source has told you.’

THE government has a “right, if necessary, to lie,” said a flunky in John F. Kennedy’s war machine. He clearly believed his own hype, because this statement was also a lie, unless the journalists who reported it agreed.

Harold Evans, the former Sunday Times editor, was mocked for urging staff to ask themselves: “Why is this bastard lying to me?” Unfortunately, many still don’t. Instead they churn out “Flat Earth News“, recycling propaganda from the state and corporations. Since Nick Davies of the Guardian coined the term, churnalism’s only got more brazen. It’s what comes of downsizing newsrooms, and upsizing demands for constant space filling. Reporters lack the time they need to find stories, never mind research them, so they rely on pre-packaged content from the PR industry.

Its multi-billion-dollar influence is insidious. Obvious falsehoods are rare, if only because they’d be too blatant. Most distortions are more cunning, using omissions, seductive narratives and sound bites to inveigle their agendas into print. Whatever the facts revealed, what matters is how they’re presented. PR flaks control access, monitor interviews, and coach clients on tailoring messages to journalists, from whose ranks they’re often poached for higher salaries. Every story needs its angle, a hook for readers and lines to keep reeling them in. PR makes these products ready for market, so the media frequently use them as supplied.

That’s not to say professionals have no standards. They just rely on what a British government propagandist called “the principle that you can report anything that a source says, regardless of its veracity, provided that you report accurately what the source has told you.” What’s true is truly irrelevant, provided all your rivals run it too.

Some once said the world wasn’t round. To argue otherwise was heresy. But even the flat earth myth had mythical elements. Many Christian scholars disputed it, long before circumnavigation. Modern mass media are just as confusing. They’re riddled with “flat earth” language, usually putting material “into context”. The views that frame a story shape its message, and whoever constructs this frame dictates the news.

A long time ago, a Chinese philosopher was asked what he’d do if he had power. Thinking it over, he said he’d start by changing the names for things. If they’re incorrect, he argued, speech does not sound reasonable, which stops things being done properly. And when things are not done properly, society’s structure is harmed. Punishments don’t fit crimes, and people don’t know what to do. The philosopher’s name was Confucius, and he’d seen how language defines what people can think.

“He was talking about Unspeak,” said a book of the same name by Steven Poole. This problem amounts to “an attempt to say something without saying it, without getting into an argument and so having to justify itself. At the same time, it tries to unspeak – in the sense of erasing, or silencing – any possible opposing point of view, by laying a claim right at the start to only one way of looking at a problem.”

Terms like “pro-life” and “tax relief” are especially economical examples, and far less crude than the Newspeak of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. How do you argue against life, or for imposing unpopular burdens? But the longer-winded tropes of “public diplomacy” carry keys to their own undoing. “You don’t have to be a specialist to resist the tide of Unspeak,” Mr Poole said: “you just have to pay attention.”

It wasn’t hard to spot, for example, that “the international community” meant America’s cohorts. Other embedded assumptions take more unpacking. The “free market” never existed. It was a construct with tariffs and terms. But because these were largely unspoken they were hard to convey. The “protectionist state-backed redistribution of wealth to shareholders at the expense of the wider world’s well-being” wouldn’t fly past sub-editors, regardless of accuracy.

Conceptual frames sneak into stories, immune from rules on sourcing or evidence. Whole slabs of this stuff are included as background, often plucked from the airwaves, or whoever pumped it out there. Much comes down to priorities. Is it more biased to frame kickback-fuelled arms sales as “Britain’s aerospace industry received a massive boost”, or to throw away the press release and cite a “massive dent to credibility on human rights”? Three guesses which angle won in busy newsrooms, including nominally crusading ones.

PR slime has smeared itself everywhere. “When I started on local papers,” Nick Davies said, “if you wanted to write a story about a hospital you phoned the hospital, you talked to the hospital manager or a doctor. Now you deal with a PR.” Companies hire them, as do charities. Even terrorists have spokesmen these days.

The industry’s so powerful that it’s co-opted half its critics. When business couldn’t call itself “sustainable”, it tried “ethical” to lure young idealists. Now executives say they’re “responsible”, spending small amounts on Good Works to offset Bad Stuff they do to get rich, and almost as much on ads to hype their whitewashed images. Corporate law, wrote the lawyer Joel Bakan, “forbids any motivation for their actions, whether to assist workers, improve the environment, or help consumers.” There’s “no legal authority to pursue such goals as ends in themselves,” only “to serve the corporation’s own interests, which generally means to maximise the wealth of its shareholders. Corporate social responsibility is thus illegal – at least when it is genuine.”

That doesn’t stop its advocates talking it up. They even use exposés as teaching aids, including the definitive Toxic Sludge is Good For You, subtitled “Lies, Damn Lies and the Public Relations Industry”. The other speciality is front groups, set up to convince us coal isn’t polluting, or that genetically modified crops could feed the world, as opposed to making money out of poor people, without other proven benefits.

Then there’s technology that’s always round the corner, such as hydrogen cars, which deterred Americans from weaning themselves off oil. Like claims denying climate change, these distant dreams were promoted by fossil fuel companies, which had seen how Big Tobacco killed passive smoking laws. They even hired the same PR firm.

PEOPLE have been conning each other for millennia, but it only became a business last century. The aim, said Edward Bernays, one of its founders, was the “engineering of consent” to manage society. Fearing revolution, he used “intelligent minorities to mould the mind of the masses” and keep them docile.

After selling World War I to American journalists, he devised a peacetime outlet for his tricks. Since he thought the interests of America and business were identical, he chose consumerism to marshal the herd. Influenced by his uncle, Sigmund Freud, he sought to stimulate inner yearnings, then sate them with consumer goods. But the creed he sold the public was subtly different. He said companies met desires that politicians couldn’t reach, making capitalism the essence of democracy.

“Propaganda got to be a bad word because of the Germans,” he explained. “So what I did is try to find some other words.” The ones he settled on were “public relations”. One of his biggest coups was getting women to smoke. The campaign began with a staged rally of “suffragettes”, lighting up what Mr Bernays called “torches of freedom”. Their pictures appeared in papers round the world, and an irrational cult of marketing was born, preying on people’s emotions to send them shopping.

Less well advertised was Mr Bernays’ role in another kind of coup. Having inspired corporations to adopt his techniques, and worked with most brances of the state, he was hired in the 1950s to demonise the government of Guatemala. This Central American nation was a banana republic, run for decades by dictators on behalf of the United Fruit Company. Then a colonel got elected democratically, promising to take back plantations and give them to peasants.

Although the new president wasn’t a Communist, Mr Bernays cast him as a Soviet pawn. A fake news agency churned out stories about the threat on America’s doorstep, and journalists took up the script. When CIA-trained rebels deposed the government, he called them freedom fighters, ignoring a string of massacres. To Mr Bernays, this was justified by the need to control people’s aspirations. Warning that the “masses promised to become king”, he favoured “regimenting the public mind every bit as much as an army regiments the bodies of its soldiers.”

He was also regimenting his own mind, which like those of American planners was focused on business, and promoting benevolent myths that cloaked its actions. “We have about 50 per cent of the world’s wealth but only 6.3 per cent of its population,” cautioned a State Department official after World War II. “Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity without positive detriment to our national security. To do so, we will have to dispense with all sentimentality and day-dreaming.” Or as another Cold Warrior put it: “If we can sell every useless article known to man in large quantities, we should be able to sell our very fine story in larger quantities.”

These officials were just affirming the national interest, which was more about products than ideas, though both helped grease the wheels of commerce. Morality had little to do with it, no matter how much it’s used to frame foreign policy, and to keep elite hands on its levers. This was a “business assault,” said Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, the American academic. Using Bernays-like brainwashing, it “helped to create a major political shift that would culminate in the election of Ronald Reagan, the subsequent tax cuts benefiting the wealthy, the elimination of regulation, and the severe cutbacks in social services.”

Swept along by prevailing currents, journalists tend to adopt official narratives, even if they personally disagree. Modern pressures of work only compound this. Since Rupert Murdoch smashed print unions, computerising and commercialising newspapers, today’s average hack writes several times as much as older peers. Even discounting new technology, that would be impossible without second-hand material from governments, companies and news agencies. Spokesmen verify stories, and attributed claims don’t need checking. Unless editors intervene, or the powerful object, demonstrable untruths become “common knowledge”.

FIGHTING back against framing ought to be easy. No propaganda works perfectly, as Victor Klemperer observed in Nazi Germany. “Whatever it is that people are determined to hide,” he wrote, “be it only from others, or from themselves, even things they carry around unconsciously – language reveals all.”

Unfortunately, this insight applies to everyone. “If you have been framed, the only response is to reframe,” suggested George Lakoff, an American linguist. “But you can’t do it in a sound bite unless an appropriate progressive language has been built up in advance.” Of course, “progressive language” is kind of Unspeak. And the ideological battleground slopes the opposite way. Hence the fable of “liberal bias”, spun by the same noise machines that skew news to suit big business and the government.

Like it or not, neutrality’s elusive. Either journalists are agents of change, or they’re someone’s useful idiots. The least radical option is to try and be accurate, even if “the truth” is inexpressible. But how are people to know when they’re being had? Websites abound with names like Source Watch, PR Watch and Corporate Watch, exposing vested interests and hidden agendas. And old news stories are full of forgotten facts, quotes and context. Searchable archives of these nuggets could help resurrect them as evidence for alternative narratives. Framing the context credibly is as vital as finding things out.

But questioning the status quo takes time. You can’t subvert pieties in 10-second sound bites. And changing how you think requires an extended break from work and “productivity”, which isn’t exactly encouraged in the average newsroom. Non-career journalists, like bloggers, are no less constrained by the economics of time, unless they’re financially secure. This in part explains the copy-and-paste nature of “independent” media. Freedom from corporate culture doesn’t abolish groupthink, nor guarantee insight, entertainment or basic accuracy. So if churnalism’s the norm wherever you turn, is reframing a solution, or part of the problem?

WORDS are weapons in a never-ending struggle for hearts and minds. But semantic reflexes form at an age when we’re unequipped for mental self-defence. Rethinking our own worldviews means challenging the programming we got at school, from wider society and off TV. Attempting this takes time as well as effort.

For journalists, undoing framing has consequences, especially if “success” correlates to expressing the “dominant” framework. It’s easier to say what people want to hear, and hard to spot that’s what you’re doing, never mind whose interests you might be serving. But how else can public lying be confronted? After Watergate, and a life listening to presidents spout fiction, the Washington Post’s Ben Bradlee concluded: “newspapers generally lie because people lie to them.” This was sometimes accidental, he thought, because truths were rarely told in their entirety. “The truth emerges, and that’s how it’s supposed to be in a democracy,” he said. “That’s still true, but seizing the pieces is getting to be harder and harder.”

The 2003 invasion of Iraq proved his point. People knew “intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy”, before leaked memos said so. When Britain published a dossier on Iraqi weapons, pundits panned the “worse than half-hearted” prose, “larded with the customary weasel words that Saddam ‘may have’ or ‘almost certainly’ does or ‘will have’ this or that”, while offering “no compelling evidence”. Yet none of these papers aired scepticism on the front page, at least not until the war was going ahead. Even those denounced by Tony Blair as “feral beasts” kept hand-wringing criticisms inside. None said he was committing “the supreme international crime” of aggression, nor called for his prosecution, or even analysed the obstacles. These didn’t warrant a mention until actors staged a trial in a London theatre.

That came fours years later, along with Alan Greenspan’s claim to be “saddened that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil.” Whether that meant controlling it, or just helping companies cash in, the press didn’t deign to report until activists scooped them. After all, Blair had declared that “the oil conspiracy theory is honestly one of the most absurd when you analyse it.” By the time he stood down, hundreds of thousands were dead, and the war had been rebranded several times. Only press stenography made this possible. When the weapons of mass non-existence weren’t found, stories were framed with claims about democracy, about anything, in fact, except occupying Iraq.

The spin-doctors learned from Napoleon. You don’t have to censor the news for effective PR. You just have to bury the truth till it no longer matters.

Raoul Djukanovic is the FT’s why do they hate us correspondent

—————————————————————————–

A lesson from America

From a 1987 talk by Ben Bradlee, the former Washington Post editor

“Now let me ask you to jump ahead some eight months to August 1964, still more than 20 years ago, to an issue of Time magazine.

“‘Through the darkness, from the West and South, the intruders boldly sped. There were at least six of them, Russian-designed Swatow gunboats armed with 37-mm and 28-mm guns, and P-4’s. At 9.52 they opened fire on the destroyers with automatic weapons, and this time from as close as 2,000 yards. The night glowed early with the nightmarish glare of air-dropped flares and boats’ searchlights. Two of the enemy boats went down.’

“That’s the kind of vivid detail that the news magazines have made famous. I don’t mean to single out Time. On the same date Life said almost the same thing and that week’s issue of Newsweek had torpedoes whipping by, U.S. ships blazing out salvo after salvo of shells. It had a PT boat bursting into flames.

“There was only one trouble. There was no battle. There was not a single intruder, never mind six of them. Never mind Russian-designed Swatow gunboats armed with 37-mm and 28-mm guns. They never opened fire. They never sank. They never fired torpedoes. They never were.”

[…]

“In case the Vietnam years have blurred in your minds, or even disappeared from your screens, may I remind you that this so-called Battle of Tonkin Gulf was the sole basis of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which was the entire justification for the United States’ war against Vietnam. This non-event happened on August 4, 1964. President Johnson went on television that very night to ask the country to support a Congressional resolution. The resolution went to Congress the next day. Two days later it was approved unanimously by the House and 88-2 by the Senate.

“The ‘facts’ behind this critically important resolution were quite simply wrong. Misinformation? Disinformation? Deceit? Whatever! Lies.”